Overview¶

- Conditional statements

- Loops and Iteration

- Function definition and function call

- Functionals

- Scoping in R

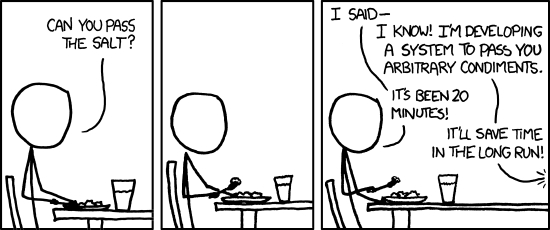

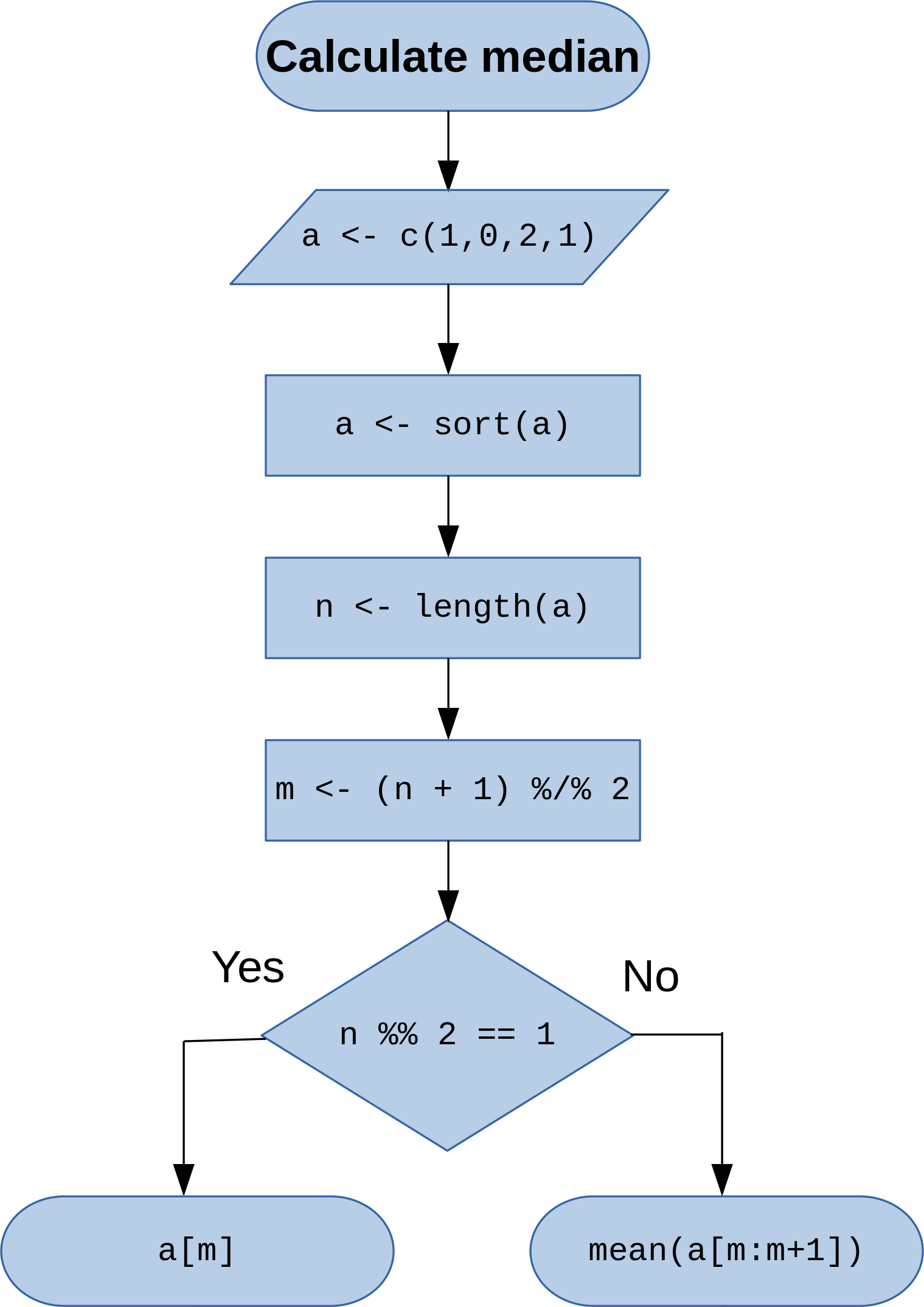

Algorithm flowchart¶

Algorithm flowchart (R)¶

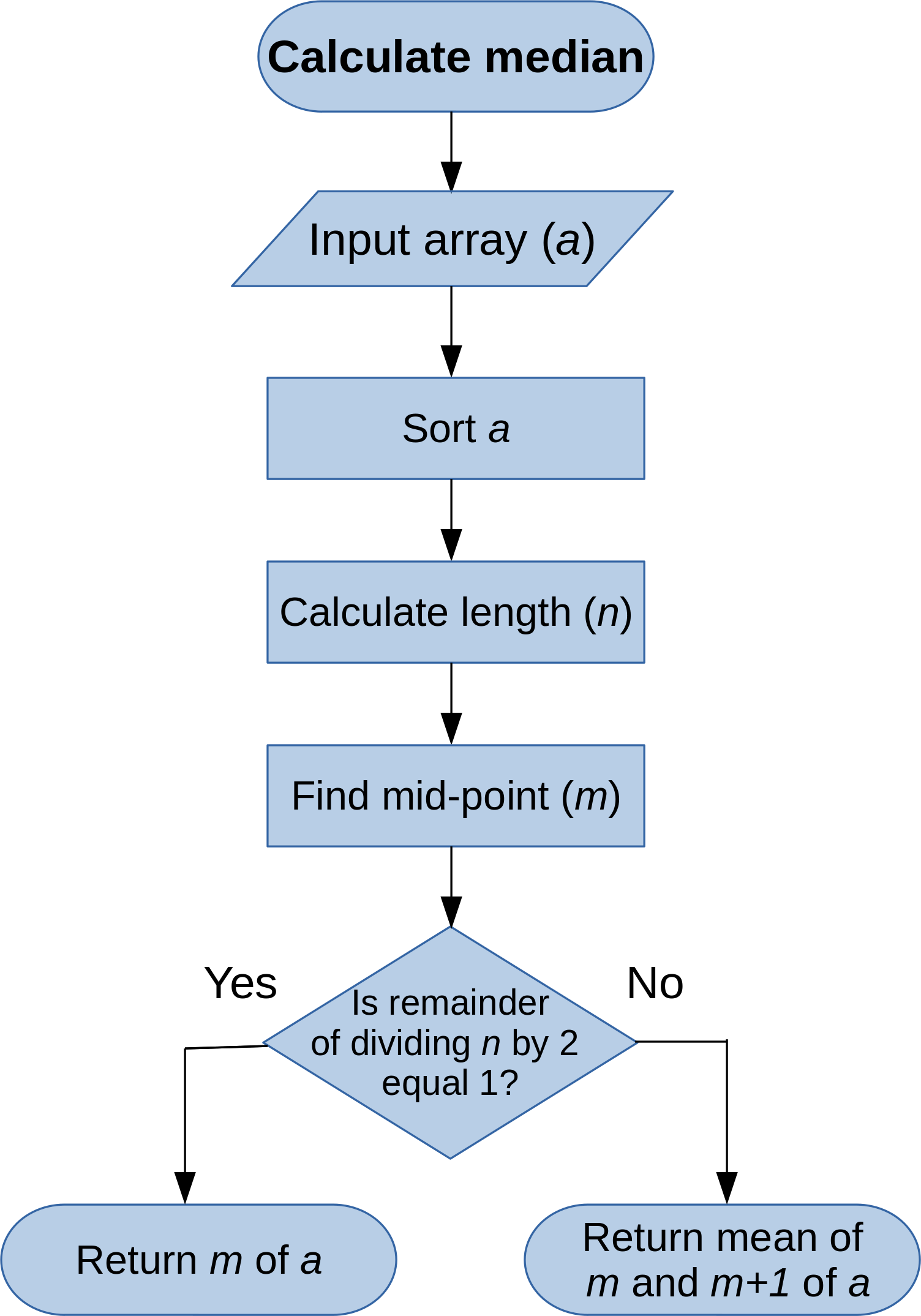

Calculate median¶

In [2]:

a <- c(1,0,2,1) # Input vector (1-dimensional array)

a <- sort(a) # Sort vector

a

[1] 0 1 1 2

In [3]:

n <- length(a) # Calculate length of vector 'a'

n

[1] 4

In [4]:

m <- (n + 1) %/% 2 # Calculate mid-point, %/% is operator for integer division

m

[1] 2

In [5]:

n %% 2 == 1 # Check whether the number of elements is odd, %% (modulo) gives remainder of division

[1] FALSE

In [6]:

mean(a[m:m+1])

[1] 1

Control flow in R¶

- Control flow is the order in which statements are executed or evaluated

- Main ways of control flow in R:

- Branching (conditional) statements (e.g.

if) - Iteration (loops) (e.g.

for) - Function calls (e.g.

length())

- Branching (conditional) statements (e.g.

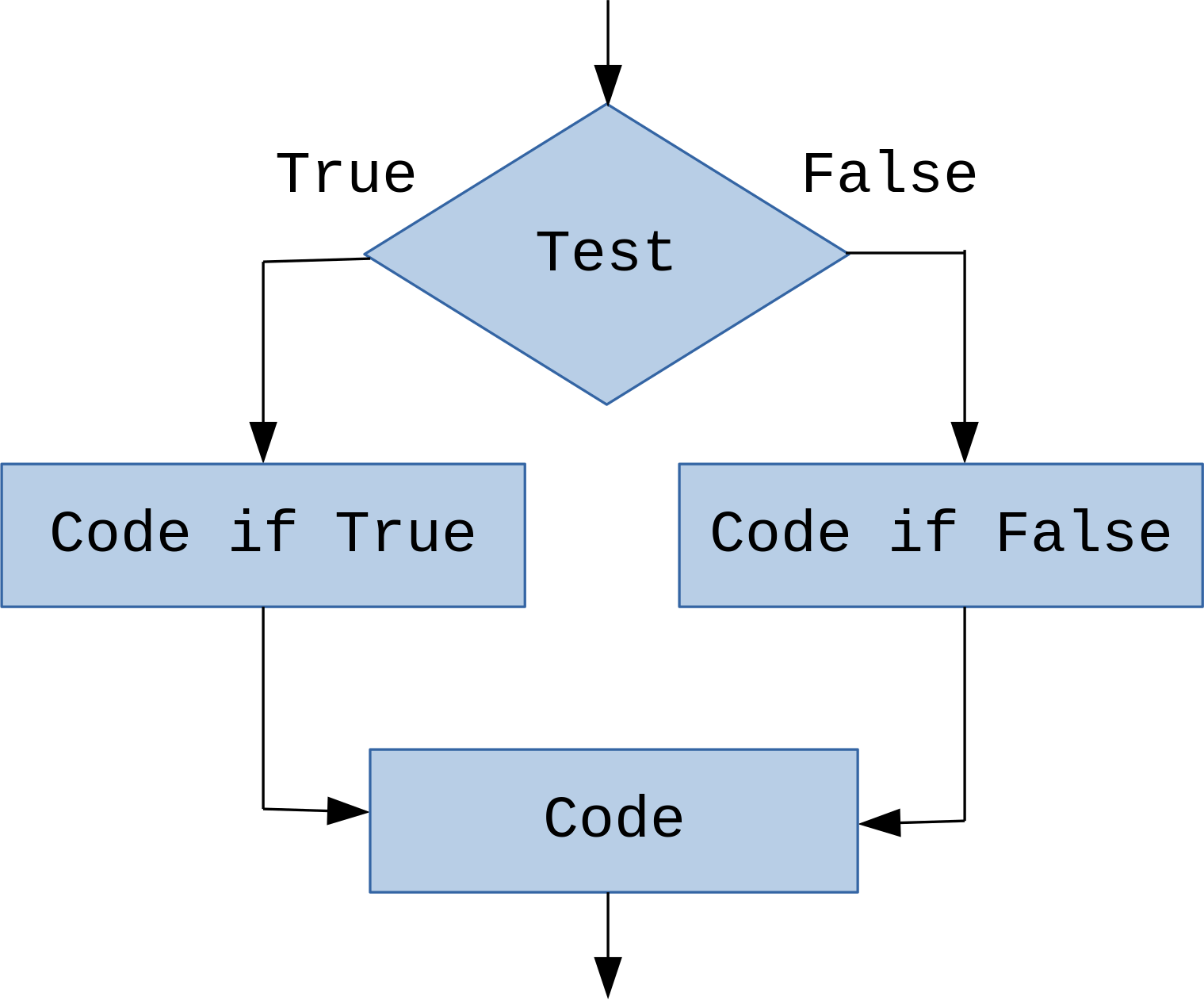

Branching programs¶

Conditional statements¶

Conditional statements: if¶

if- defines condition under which some code is executed

if (<boolean_expression>) {

<some_code>

}In [7]:

a <- c(1, 0, 2, 1, 100)

a <- sort(a)

n <- length(a)

m <- (n + 1) %/% 2

if (n %% 2 == 1) {

a[m]

}

[1] 1

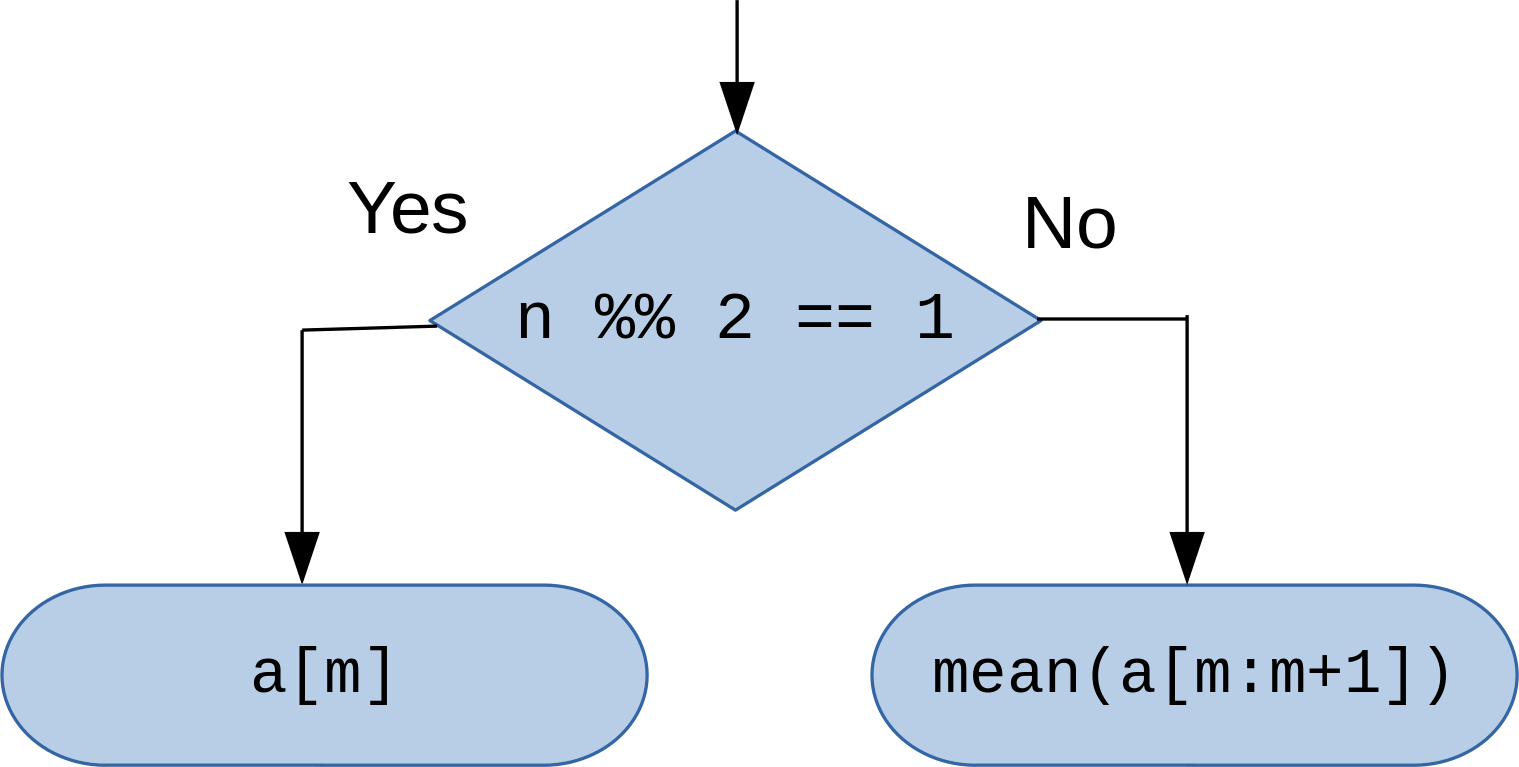

Conditional statements: if - else¶

if - else- defines both condition under which some code is executed and alternative code to execute

if (<boolean_expression>) {

<some_code>

} else {

<some_other_code>

}In [8]:

a <- c(1, 0, 2, 1)

a <- sort(a)

n <- length(a)

m <- (n + 1) %/% 2

if (n %% 2 == 1) {

a[m]

} else {

mean(a[m:m+1])

}

[1] 1

Conditional statements: if - else if - else¶

if - else if - ... - else- defines both condition under which some code is executed and several alternatives

if (<boolean_expression>) {

<some_code>

} else if (<boolean_expression>) {

<some_other_code>

} else if (<boolean_expression>) {

...

...

} else {

<some_more_code>

}Example of longer conditional statement¶

In [9]:

x <- 42

if (x > 0) {

print("Positive")

} else if (x < 0) {

print("Negative")

} else {

print("Zero")

}

[1] "Positive"

Optimising conditional statements¶

- Parts of conditional statement are evaluated sequentially, so it makes sense to put the most likely condition as the first one

In [10]:

# Ask for user input and cast as double

num <- as.double(readline("Please, enter a number:"))

if (num %% 2 == 0) {

print("Even")

} else if (num %% 2 == 1) {

print("Odd")

} else {

print("This is a real number")

}

Please, enter a number:43 [1] "Odd"

Nesting conditional statements¶

- Conditional statements can be nested within each other

- But consider code legibility 📜, modularity ⚙️ and speed 🏎️

In [11]:

num <- as.integer(readline("Please, enter a number:")) # Ask for user input and cast as integer

if (num > 0) {

if (num %% 2 == 0) {

print("Positive even")

} else {

print("Positive odd")

}

} else if (num < 0) {

if (num %% 2 == 0) {

print("Negative even") # Notice that odd/even check appears twice

} else {

print("Negative odd") # Consider abstracting this as a function

}

} else {

print("Zero")

}

Please, enter a number:-43 [1] "Negative odd"

ifelse() function¶

- R also provides a vectorized version of

if - elseconstruct - It takes a vector as an input and returns another vector as an output

ifelse(<boolean_expression>, <if_true>, <if_false>)In [12]:

num <- 1:10

num

[1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

In [13]:

ifelse(num %% 2 == 0, "even", "odd")

[1] "odd" "even" "odd" "even" "odd" "even" "odd" "even" "odd" "even"

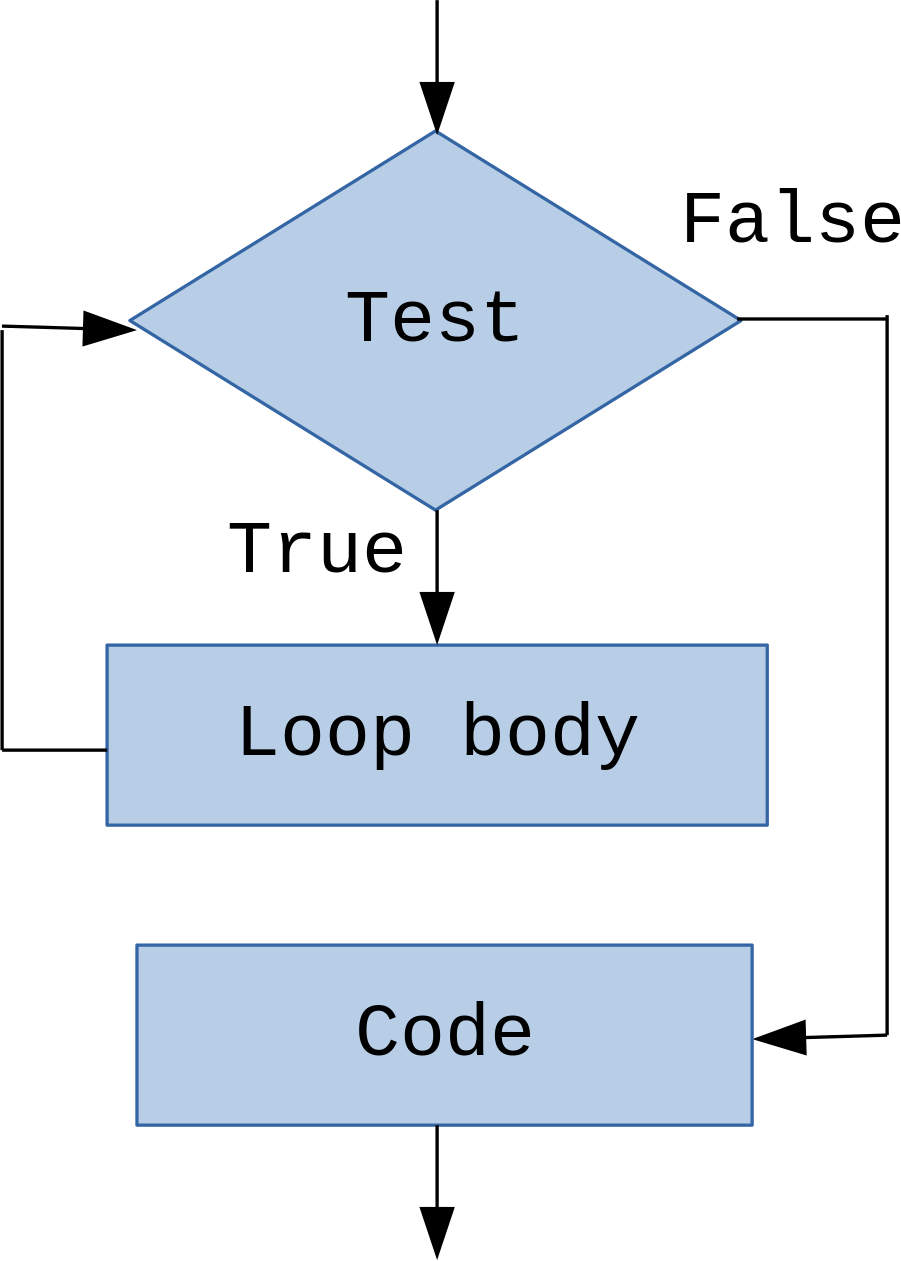

Iteration (looping)¶

Iteration: while¶

while- defines a condition under which some code (loop body) is executed repeatedly

while (<boolean_expression>) {

<some_code>

}In [14]:

# Calculate a factorial with decrementing function

# E.g. 5! = 1 * 2 * 3 * 4 * 5 = 120

x <- 5

factorial <- 1

while (x > 0) {

factorial <- factorial * x

x <- x - 1

}

factorial

[1] 120

Iteration: for¶

for- defines elements and sequence over which some code is executed iteratively

for (<element> in <sequence>) {

<some_code>

}In [15]:

x <- seq(5)

factorial <- 1

for (i in x) {

factorial <- factorial * i

}

factorial

[1] 120

Iteration with conditional statements¶

In [16]:

# Find maximum value in a vector with exhaustive enumeration

v <- c(3, 27, 9, 42, 10, 2, 5)

max_val <- v[1]

for (i in v) {

if (i > max_val) {

max_val <- i

}

}

max_val

[1] 42

Generating sequences for iteration¶

seq()function that we encountered in subsetting can be used in looping- As well as its cousins:

seq_len()andseq_along()

seq(<from>, <to>, <by>)

seq_len(<length>)

seq_along(<object>)Generating sequences for iteration examples¶

In [17]:

# If by argument is omitted, it defaults to 1

s <- seq(25, 44)

s

[1] 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44

In [18]:

# seq_len() is equivalent to seq(1, length(<object>))

seq_len(length(s))

[1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

In [19]:

seq_along(s)

[1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

In [20]:

# The sequence that you are supplying to seq_along() doesn't have to be numeric

seq_along(letters[1:20])

[1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

Generating sequences for iteration examples continued¶

In [21]:

# vector() function is useful for initiliazing empty vectors of known type and length

s2 <- vector(mode = "double", length = length(s))

for (i in seq_len(length(s))) {

s2[i] <- s[i] * 2

}

In [22]:

s2

[1] 50 52 54 56 58 60 62 64 66 68 70 72 74 76 78 80 82 84 86 88

In [23]:

s3 <- vector(mode = "double", length = length(s))

for (i in seq_along(s)) {

s3[i] <- s[i] * 3

}

In [24]:

s3

[1] 75 78 81 84 87 90 93 96 99 102 105 108 111 114 117 120 123 126 129 [20] 132

Iteration: break and next¶

break- terminates the loop in which it is containednext- exits the iteration of a loop in which it is contained

In [25]:

for (i in seq(1,6)) {

if (i %% 2 == 0) {

break

}

print(i)

}

[1] 1

In [26]:

for (i in seq(1,6)) {

if (i %% 2 == 0) {

next

}

print(i)

}

[1] 1 [1] 3 [1] 5

Infinite loop¶

Infinite loops¶

- Loops that have no explicit limits for the number of iterations are called infinite

- They have to be terminated with a

breakstatement (or Ctrl/Cmd-C in interactive session) - Such loops can be unintentional (bug) or desired (e.g. waiting for user's input, some event)

In [27]:

i <- 1

while (TRUE) {

i <- i + 1

if (i > 10) {

break

}

}

In [28]:

i

[1] 11

Iteration: repeat¶

repeat- defines code which is executed iteratively until the loop is explicitly terminated- Is equivalent to

while (TRUE)

repeat {

<some_code>

}In [29]:

i <- 1

repeat {

i <- i + 1

if (i > 10) {

break

}

}

In [30]:

i

[1] 11

Decomposition and abstraction¶

- So far: built-in types, assignments, branching and looping constructs

- In principle, any problem can be solved just with those

- But a solution would be non-modual and hard-to-maintain

- Functions provide decomposition and abstraction

Functions in R¶

- Function call is the centerpiece of computation in R

- It involves function object and objects that are supplied as arguments

- Functions in R do not have side-effects (nonlocal modifications of input objects)

- In R we use function

function()to create a function object - Functions are also referred to as closures in some R documentation

<function_name> <- function(<arg_1>, <arg_2>, ..., <arg_n>) {

<function_body>

}In [31]:

foo <- function(arg) {

# <function_body>

}

Function components¶

- Body (

body()) - code inside the function - List of arguments (

formals()) - controls how function is called - Environment/scope/namespace (

environment()) - location of function's definition and variables

Function components example¶

In [32]:

is_positive <- function(num) {

if (num > 0) {

return(TRUE)

} else {

return(FALSE)

}

}

In [33]:

body(is_positive)

{

if (num > 0) {

return(TRUE)

}

else {

return(FALSE)

}

}

In [34]:

formals(is_positive)

$num

In [35]:

environment(is_positive)

<environment: R_GlobalEnv>

Function call¶

- Function is executed until:

- Either

return()function is encountered - There are no more expressions to evaluate

- Either

- Function call always returns a value:

- Argument of

return()function call - Value of last expression if no

return()(implicit return)

- Argument of

- Function can return only one object

- But you can combine multiple R objects in a list

Function call example¶

In [36]:

is_positive <- function(num) {

if (num > 0) {

res <- TRUE

} else {

res <- FALSE

}

return(res)

}

In [37]:

res_1 <- is_positive(5)

res_2 <- is_positive(-7)

In [38]:

print(res_1)

print(res_2)

[1] TRUE [1] FALSE

Implicit return example¶

In [39]:

is_positive <- function(num) {

if (num > 0) {

res <- TRUE

} else {

res <- FALSE

}

res

}

In [40]:

res_1 <- is_positive(5)

res_2 <- is_positive(-7)

In [41]:

print(res_1)

print(res_2)

[1] TRUE [1] FALSE

Implicit return example continued¶

In [42]:

# While this function provides the same functionality as the two versions above

# This is an example of a bad programming style, return value is very unintuitive

is_positive <- function(num) {

if (num > 0) {

res <- TRUE

} else {

res <- FALSE

}

}

In [43]:

res_1 <- is_positive(5)

res_2 <- is_positive(-7)

In [44]:

print(res_1)

print(res_2)

[1] TRUE [1] FALSE

Function arguments¶

- Arguments provide a way of giving input to a function

- Arguments in function definition are formal arguments

- Arguments in function invocations are actual arguments

- When a function is invoked (called) arguments are matched and bound to local variable names

- R matches arguments in 3 ways:

- by exact name

- by partial name

- by position

- It is a good idea to only use unnamed (positional) for the main (first one or two) arguments

Function arguments example¶

In [45]:

format_date <- function(day, month, year, reverse = TRUE) {

if (isTRUE(reverse)) {

formatted <- paste(

as.character(year), as.character(month), as.character(day), sep = "-"

)

} else {

formatted <- paste(

as.character(day), as.character(month), as.character(year), sep = "-"

)

}

return(formatted)

}

In [46]:

format_date(4, 10, 2021)

[1] "2021-10-4"

In [47]:

format_date(y = 2021, m = 10, d = 4) # Technically correct, but rather unintuitive

[1] "2021-10-4"

In [48]:

format_date(y = 2021, m = 10, d = 4, FALSE) # Technically correct, but rather unintuitive

[1] "4-10-2021"

In [49]:

format_date(day = 4, month = 10, year = 2021, FALSE)

[1] "4-10-2021"

Nested functions¶

In [50]:

which_integer <- function(num) {

even_or_odd <- function(num) {

if (num %% 2 == 0) {

return("even")

} else {

return("odd")

}

}

eo <- even_or_odd(num)

if (num > 0) {

return(paste0("positive ", eo))

} else if (num < 0) {

return(paste0("negative ", eo))

} else {

return("zero")

}

}

In [51]:

which_integer(-43)

[1] "negative odd"

In [52]:

even_or_odd(-43)

Error in even_or_odd(-43): could not find function "even_or_odd" Traceback:

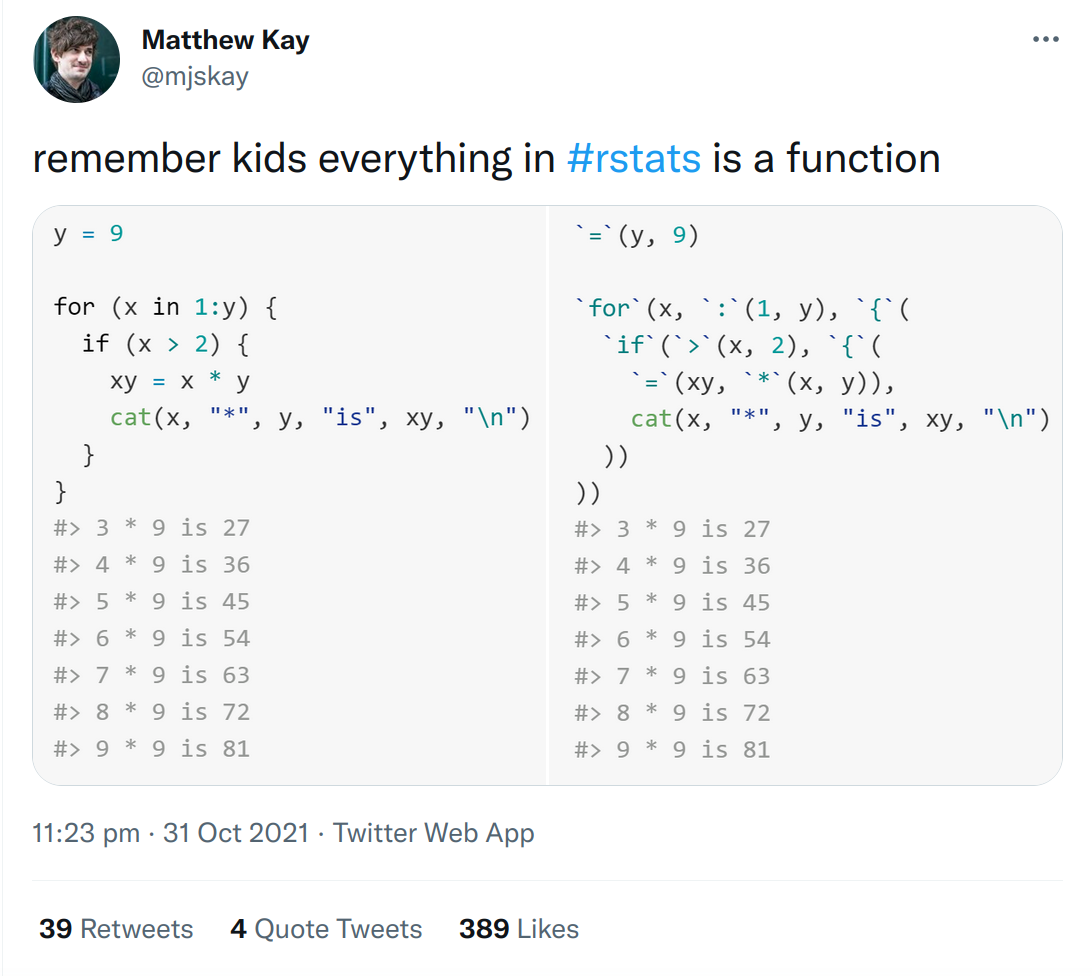

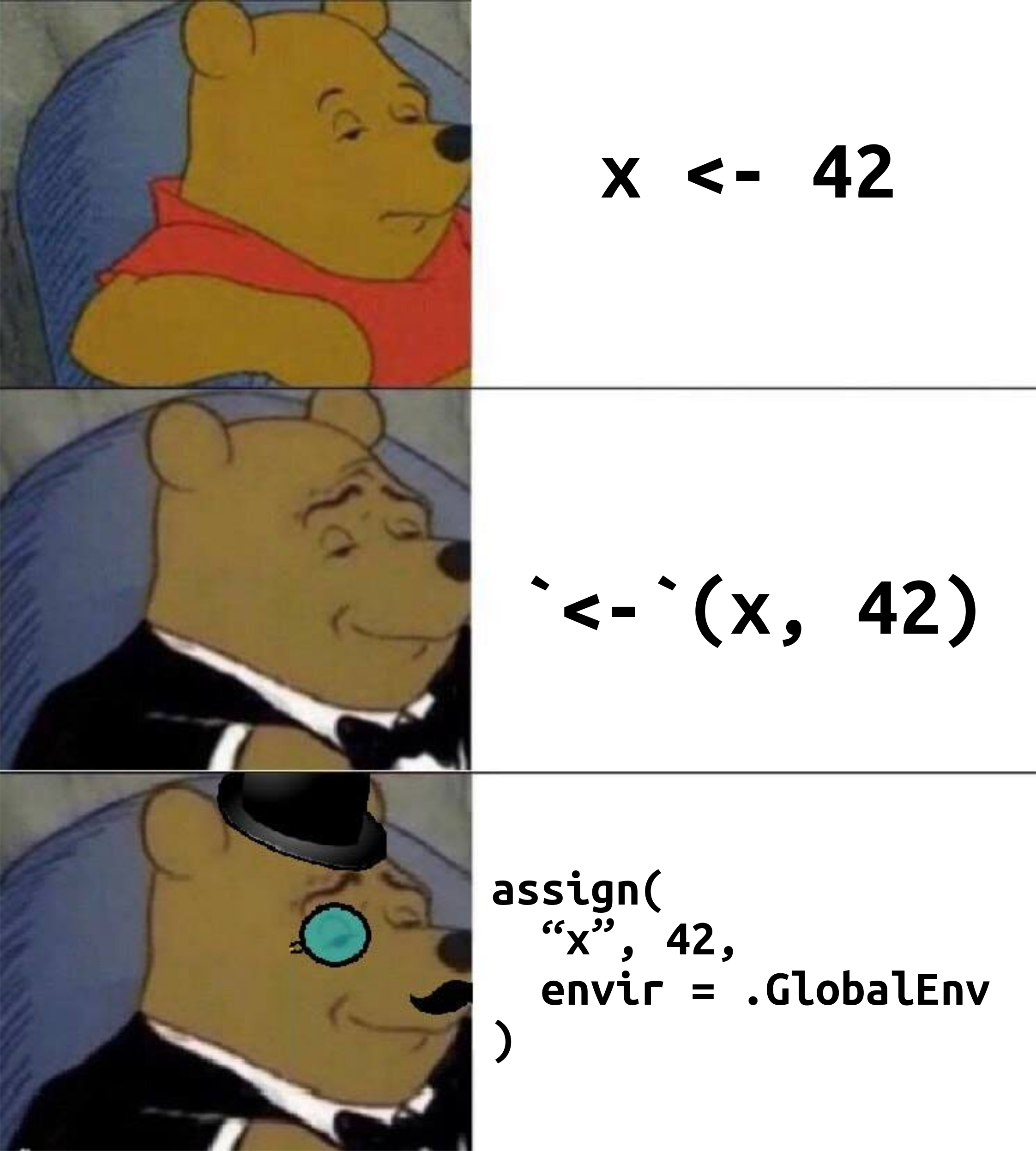

R environment basics¶

- Variables (aka names) exist in an environment (aka namespace/scope in Python)

- The same R object can have different names

- Binding of objects to names (assignment) happens within a specific environment

- Most environments get created by function calls

- Approximate hierarchy of environments:

- Execution environment of a function

- Global environment of a script

- Package environment of any loaded packages

- Base environment of base R objects

R environment example¶

In [53]:

x <- 42

# is equivalent to:

# Binding R object '42', double vector of length 1, to name 'x' in the global environment

assign("x", 42, envir = .GlobalEnv)

x

[1] 42

In [54]:

x <- 5

foo <- function() {

x <- 12

return(x)

}

y <- foo()

print(y)

print(x)

[1] 12 [1] 5

Examples of operators as function calls¶

In [55]:

`+`(3, 2) # Equivalent to: 3 + 2

[1] 5

In [56]:

`<-`(x, c(10, 12, 14)) # x <- c(10, 12, 14)

x

[1] 10 12 14

In [57]:

`[`(x, 3) # x[3]

[1] 14

In [58]:

`>`(x, 10) # x > 10

[1] FALSE TRUE TRUE

Anonymous functions¶

- While R has no special syntax for creating anonymous (aka lambda in Python) function

- Note that the result of

function()does not have to be assigned to a variable - Thus function

function()can be easily incorporate into other function calls

In [59]:

add_five <- function() {

return(function(x) x + 5)

}

af <- add_five()

In [60]:

af # 'af' is just a function, which is yet to be invoked (called)

function(x) x + 5 <environment: 0x55baf8cccac0>

In [61]:

af(10) # Here we call a function and supply 10 as an argument

[1] 15

In [62]:

# Due to vectorized functions in R this example is an obvious overkill (seq(10) ^ 2 would do just fine)

# but it shows a general approach when we might need to apply a non-vectorized functions

sapply(seq(10), function(x) x ^ 2)

[1] 1 4 9 16 25 36 49 64 81 100

Functionals¶

- Functionals are functions that take other functions as one of their inputs

- Due to R's functional nature, functionals are frequently used for many tasks

apply()family of base R functionals is the most ubiquitous example- Their most common use case is an alternative of for loops

- Loops in R have a reputation of being slow (not always warranted)

- Functionals also allow to keep code more concise

Functional example¶

In [63]:

# Applies a supplied function to a random draw

# from the normal distribution with mean 0 and sd 1

functional <- function(f) { f(rnorm(10)) }

In [64]:

functional(mean)

[1] 0.3186378

In [65]:

functional(median)

[1] -0.2481884

In [66]:

functional(sum)

[1] 1.492055

Summary of common apply() functions¶

| Function | Description | Input Object | Output Object | Simplified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

apply() |

Apply a given function to margins (rows/columns) of input object | matrix/array/data.frame | vector/matrix/array/list | Yes |

lapply() |

Apply a given function to each element of input object | vector/list | list | No |

sapply() |

Same as lapply(), but output is simplified |

vector/list | vector/matrix | Yes |

vapply() |

Same as sapply(), but data type of output is specified |

vector/list | vector | No |

mapply() |

Multivariate version of sapply(), takes multiple objects as input |

vectors/lists | vector/matrix | Yes |

lapply() function¶

- Takes a function and a vector or list as input

- Applies the input function to each element in the list

- Returns list as an onput

lapply(<input_object>, <function_name>, <arg_1>, ..., <arg_n>)lapply() examples¶

In [67]:

l <- list(a = 1:2, b = 3:4, c = 5:6, d = 7:8, e = 9:10)

In [68]:

# Apply sum() to each element of list 'l'

lapply(l, sum)

$a [1] 3 $b [1] 7 $c [1] 11 $d [1] 15 $e [1] 19

In [69]:

# We can exploit the fact that basic operators are function calls

# Here, each subsetting operator `[` with argument 2 is applied to each element

# Which gives us second element within each element of the list

lapply(l, `[`, 2)

$a [1] 2 $b [1] 4 $c [1] 6 $d [1] 8 $e [1] 10

apply() function¶

- Works with higher-dimensional (> 1d) input objects (matrices, arrays, data frames)

- Is a common tool for calculating summaries of rows/columns

<margin>argument indicates whether function is applied across rows (1) or columns (2)

apply(<input_object>, <margin>, <function_name>, <arg_1>, ..., <arg_n>)apply() examples¶

In [70]:

m <- matrix(1:12, nrow = 3, ncol = 4)

m

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [1,] 1 4 7 10 [2,] 2 5 8 11 [3,] 3 6 9 12

In [71]:

# Sum up rows (can also be achieved with rowSums() function)

apply(m, 1, sum)

[1] 22 26 30

In [72]:

# Calculate averages across columns (also available in colMeans())

apply(m, 2, mean)

[1] 2 5 8 11

In [73]:

# Find maximum value in each column

apply(m, 2, max)

[1] 3 6 9 12

mapply() function¶

- Takes a function and multiple vectors or lists as input

- Applies the function to each corresponding element of input sequences

- Simplifies output into vector (if possible)

mapply(<function_name>, <input_object_1>, ..., <input_object_n>, <arg_1>, ..., <arg_n>)mapply() examples¶

In [74]:

means <- -2:2

sds <- 1:5

In [75]:

# Generate one draw from a normal distribution where

# each mean is an element of vector 'means'

# and each standard deivation is an element of vector 'sds'

#

# rnorm(n, mean, sd) takes 3 arguments: n, mean, sd

mapply(rnorm, 1, means, sds)

[1] -0.7043966 -2.9181125 0.7705752 0.8115289 4.9755344

In [76]:

# While simplification of output

# (attempt to collapse it in fewer dimensions)

# makes hard to predict the object returned

# by apply() functions that have simplified = TRUE by default

mapply(rnorm, 5, means, sds)

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [1,] -3.058834 -1.0853410 -0.08222913 -0.6397508 1.8098831 [2,] -2.759082 -3.6308276 -1.53727082 1.4870609 -0.4620664 [3,] -1.633935 -0.1775828 -3.99636499 2.7069711 4.1554896 [4,] -1.241012 -1.8139769 -0.35165313 5.2904383 11.1715264 [5,] -1.227846 -1.5496606 2.82421174 5.9838118 4.9411164

Packages¶

- Program can access functionality of a package using

library()function - Every package has its own namespace (which can accessed with

::)

library(<package_name>)

<package_name>::<object_name>Package loading example¶

In [77]:

# Package 'Matrix' is part of the standard R library and doesn't have to be installed separately

library("Matrix")

In [78]:

# While it is possible to just use function sparseVector() after loading the library,

# it is good practice to state explicitly which package the object is coming from.

sv <- Matrix::sparseVector(x = c(1, 2, 3), i = c(3, 6, 9), length = 10)

In [79]:

sv

sparse vector (nnz/length = 3/10) of class "dsparseVector" [1] . . 1 . . 2 . . 3 .

Next¶

- Data wrangling